UK Government no longer a ‘Global Charity’, new aid minister to tell MPs

The British Government will no longer act as a “global charity”, the new aid minister is expected to tell members of Parliament when she appears before a Commons committee on tuesday. In her first major appearance since assuming the role, Baroness Jenny Chapman will set out a decisive shift in the UK’s approach to overseas aid, marking a move away from what critics have described as a donor-recipient model to one emphasising strategic partnerships and knowledge-sharing.

Baroness Chapman, who was appointed to the role in february following the resignation of Anneliese Dodds, will appear before the commons international development Committee. Her predecessor, Ms Dodds, resigned from the post in protest at the Government’s controversial decision to reduce the UK’s overseas aid budget, redirecting funds towards defence spending instead.

The Labour peer is expected to make it clear that while the Government remains committed to international development, its priorities have changed. In a prepared statement, she is likely to tell MPs: “The days of viewing the UK Government as a global charity are over.”

The minister will argue that in a world of constrained resources, the UK needs to prioritise efficiency, effectiveness, and outcomes over the traditional approach of simply allocating financial aid. “We have to get the best value for money, for the UK taxpayer, but also for the people we are trying to help around the world,” she will say.

The shift in tone and policy comes in the wake of a reduction in the international development budget, which earlier this year was cut from 0.5% of gross national income (GNI) to 0.3%. The reduction was heavily criticised by humanitarian organisations and opposition parties, who warned it would result in significant cuts to life-saving programmes in the world’s poorest regions.

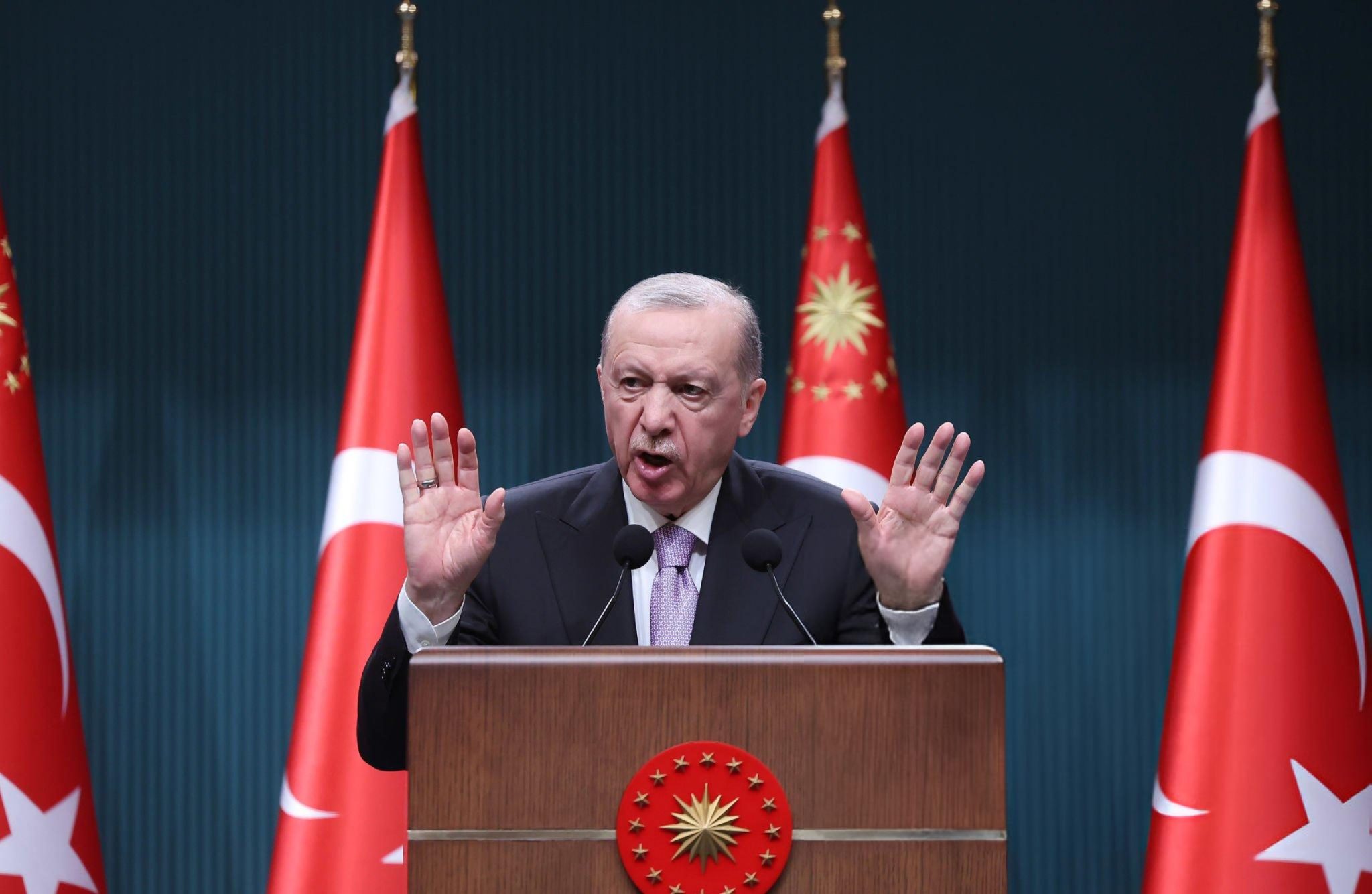

Critics drew comparisons with the actions of former US President Donald Trump, whose administration drastically curtailed the budget and mandate of the US Agency for International Development. They argued that such cuts risk undermining the progress made over decades in areas such as child immunisation, maternal health, and poverty alleviation.

However, Baroness Chapman is expected to defend the cutbacks as part of a necessary recalibration of the UK’s role on the global stage. She will highlight a need to pivot towards an approach of “partnering, not paternalism,” pointing to existing collaborations, such as a deal between the UK’s Met Office and its Bangladeshi counterpart, aimed at improving flood forecasting and resilience.

“We need to support other countries’ systems where this is what they want, so they can educate their children, reform their own healthcare systems and grow their economies in ways which last,” she will say. “And, ultimately, exit the need for aid.”

Baroness Chapman will further argue that the focus of British development policy must be on long-term outcomes that empower countries to become self-sufficient, rather than on headline-grabbing aid pledges. “With less to spend, we have no choice. Biggest impact and biggest spend aren’t always the same thing,” she is expected to tell the committee.

Her appearance comes at a time when the Government is seeking to balance domestic pressures, such as economic constraints and defence commitments, with its responsibilities on the global stage. While ministers insist that the UK will remain a key player in international development, aid agencies warn that the shift in policy risks abandoning millions of people who still rely on British support for basic services.

Nonetheless, Baroness Chapman’s statements are likely to reinforce the Government’s determination to recast its role from that of a benefactor to a strategic partner, focusing on leveraging British expertise, science, and innovation to support development in a way that is seen as more sustainable and mutually beneficial.