Europe’s Groundwater Is Running Out: What Happened, Why It Matters, and What Must Be Done

Across Europe, groundwater — the invisible freshwater that supplies towns, farms and ecosystems — is under unprecedented pressure. Scientists, satellite data and pan-European monitoring all point to a worrying pattern: in large swathes of the continent groundwater stores are shrinking, recharge is failing to keep pace with withdrawals, and pressure on aquifers is increasing. The trend matters for everyone, from farmers in southern Spain to residents who rely on boreholes and public supply in southeast England — including Westferry. European Environment Agency+1

This article explains, in plain terms, what’s happening, why it’s happening (the science), who is affected, what governments must plan, and what residents in Westferry should watch and do. Sources and references are listed so readers can check the underlying science and policy material — and be confident this is original reporting, not reproduced copyrighted text.

What exactly has occurred?

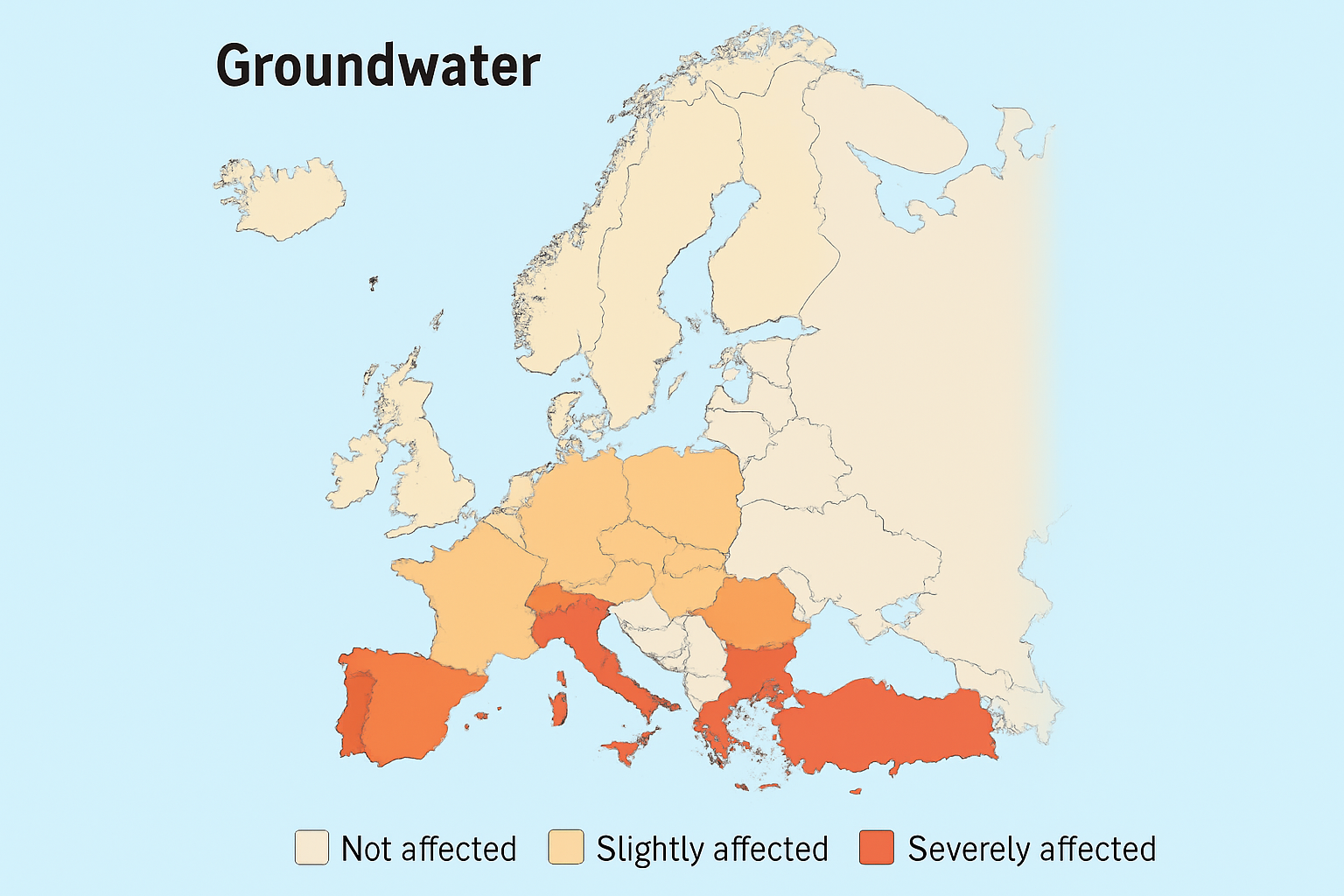

Multiple lines of evidence from monitoring wells, satellite gravimetry and environmental reporting show that many European aquifers have experienced net water losses over the last two decades. Declines are especially clear in southern and central Europe — parts of Spain, Italy and across the Euro-Mediterranean region — but some localised hotspots of depletion also exist in western and central regions. Long-term averages show negative groundwater-storage trends in much of the Euro-Mediterranean area. Nature+1

At the same time, European monitoring (EEA, national river basin plans and new continental databases) shows elevated abstraction pressure in many groundwater bodies and that pollution (notably nitrates and pesticides) compounds the problem by reducing usable supplies. European Environment Agency+1

The scientific reasons — what’s driving the decline?

The decline has three interacting causes:

- Climate change and altered precipitation patterns. Warmer air holds more moisture but also accelerates evaporation. Europe is seeing more intense downpours and longer dry spells in many regions; when rain falls in heavy bursts it often runs off rather than recharging the soil and aquifers, reducing the slow infiltration that refills groundwater. This shift reduces natural recharge. The Guardian+1

- Over-abstraction for agriculture, industry and public supply. In dry years farmers rely on groundwater for irrigation; towns and industry also pump more when surface water is low. Where withdrawals exceed recharge for months or years, water tables fall and aquifer storage declines. Large irrigated croplands are a particular hotspot for depletion. Nature+1

- Land-use change and pollution reducing aquifer function. Urbanisation, soil sealing and contaminants (nitrates, pesticides) change how water infiltrates soils and degrade water quality, meaning that even where volumes exist they are less usable without costly treatment. European Environment Agency+1

Combined, these processes produce long-term loss of groundwater storage in many areas: not every aquifer everywhere is “running out” at the same rate, but for many local systems the headroom to absorb future dry years is shrinking. SpringerLink+1

Who is affected — and how severe is it?

- Agriculture: Irrigation-dependent farms face reduced yields, higher costs and a greater need to drill deeper wells. In southern Europe, water restrictions and rationing have already occurred in drought years. Financial Times

- Public water supply: In some regions (including parts of southeast England) groundwater provides the majority of drinking water; sustained declines increase the risk of shortages and higher treatment costs. The Guardian

- Ecosystems: Wetlands, rivers and dependent species suffer when groundwater levels fall, sometimes causing permanent habitat loss. European Environment Agency

- Economy & communities: Reduced water reliability raises costs, discourages investment in water-intensive industries, and can force relocation or retrenchment of businesses. waternewseurope.com

Severity varies: some aquifers show modest seasonal variation and recover in wet years; others show persistent long-term decline that signals structural unsustainability. Nature

What governments should plan and do — practical policy steps

Addressing groundwater stress requires joined-up policies across water, land and climate planning. Key priorities governments should adopt are:

- Quantified groundwater budgets and transparent monitoring. Establish and fund high-resolution, publicly accessible groundwater monitoring (piezometers, remote sensing, and integrated databases) so policymakers and the public know which aquifers are sustainable and which are over-drawn. (This is already recommended in EEA reporting and ongoing monitoring initiatives.) European Environment Agency+1

- Enforceable abstraction limits based on science. Where monitoring shows unsustainable drawdown, legally enforceable caps — tied to replenishment rates — must be set and applied, with fair trading, metering and clear penalties for non-compliance. SpringerLink

- Water-smart agriculture and demand reduction. Shift subsidies and incentives toward efficient irrigation (precision irrigation, deficit irrigation), drought-resilient crops, soil health practices that improve infiltration, and water reuse / treated wastewater schemes. Reducing agricultural groundwater demand is central because crop production is a major user. ScienceDirect+1

- Nature-based recharge and catchment restoration. Restore wetlands, re-naturalise floodplains and increase permeable surfaces in urban areas to slow runoff and boost infiltration where geology permits. These are low-regret, co-benefit investments for biodiversity and flood resilience. European Environment Agency

- Infrastructure investments in water storage and reuse. Where appropriate, build decentralized storage, invest in leakage reduction in distribution networks, and expand water recycling for industry — recognising that large reservoirs are not always the right solution and that they take time to deliver. The Guardian+1

- Cross-sector governance and fair allocation. Align policies across agriculture, urban planning, energy and environment. Ensure vulnerable communities and small users are protected, and design compensation or transition support for sectors affected by abstraction limits. European Environment Agency

- Long-term climate adaptation planning. Integrate groundwater resilience in national adaptation strategies, using scenarios that reflect increased drought frequency and variability. European Environment Agency

What residents and local communities (including Westferry) should do

Even urban communities like Westferry have a role to play:

- Reduce household demand. Fit water-efficient appliances, fix leaks, use low-flow taps and toilets, and adopt secondary uses (e.g., reuse greywater for irrigation of communal planters). Small per-household savings add up fast in dense urban areas.

- Support local nature-based solutions. Advocate for permeable paving, green roofs, tree-planting and street-level measures that slow runoff and increase local infiltration where geology allows. These measures also improve urban cooling and air quality.

- Engage with water planning. Attend local consultations, ask councils about water resilience plans, and push for transparent reporting on how public supply systems will manage lower groundwater availability.

- Community resilience planning. For flats and businesses dependent on reliable water (e.g., restaurants), have contingency plans, store emergency water where appropriate, and join local groups to share information and lobbying power.

- Support policy change. Elect and press for representatives who prioritise sustainable water management and back the investments outlined above.

Westferry’s particular concern is more indirect but real: although the neighbourhood uses Thames water (a largely surface and mixed supply), many of the region’s supply chains, food distribution and regional industry depend on groundwater stability elsewhere in the UK and Europe. If supply chains are disrupted, or if national water policy leads to higher costs, Westferry’s residents and businesses will feel the impact. The Guardian+1

Local reasoning for Westferry Times: why this matters here

Westferry sits at the economic edge of Canary Wharf and the Docklands. The area depends on a healthy regional economy, stable utility services and predictable costs to attract and retain businesses and residents. Groundwater decline — though geographically patchy — matters to Westferry because:

- Supply chain exposure: Food, construction materials and many services that support Westferry’s economy come from regions reliant on groundwater. Disruption in agricultural supply or price spikes hit consumers and businesses here. Nature

- Investor confidence: Long-term infrastructure and property investment decisions factor national and regional resource security; visible water stress can lower investor appetite and slow development. waternewseurope.com

- Policy ripple effects: If national governments impose strict abstraction caps or emergency drought measures, urban water policies (including restrictions or price signals) can change quickly and affect household budgets and businesses. Westferry is not immune. European Environment Agency

For Westferry, the practical takeaway is to press for transparent regional water planning, support city-level resilience measures, and recognise that local prosperity increasingly depends on sustainable resource governance beyond the neighbourhood’s immediate boundaries.

How bad is it — are we near “running out”?

“Running out” is a blunt phrase. In many places Europe still has usable groundwater; in some areas aquifers are healthy and even showing increases. But the pattern of widespread loss in the Euro-Mediterranean, accelerating drawdowns in irrigated areas, and growing abstraction pressure is a clear red flag. Without corrective action — scientifically based abstraction limits, water-efficient agriculture, rapid investments in reuse and conservation — more aquifers will cross sustainability thresholds and local shortages will become more frequent and severe. SpringerLink+1

Further reading and references

Below are the main sources used to compile this article. They are public reports and peer-reviewed studies that you can consult for more detail:

- European Environment Agency — Europe’s State of Water 2024: The need for improved water resilience. Overview of chemical and quantitative status of surface and groundwater across reporting EU countries. European Environment Agency

- The Guardian (analysis, Nov 2025) — “Revealed: Europe’s water reserves drying up due to climate breakdown”. Recent reporting synthesising satellite and monitoring data. The Guardian

- Jasechko et al., Nature (2024) — “Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in the twenty-first century”. A large analysis of groundwater-level trends globally and regionally. Nature

- Xanke et al., Hydrogeology Journal / Springer (2021) — “Quantification and possible causes of declining groundwater in the Euro-Mediterranean region”. Satellite-based quantification of groundwater storage trends. SpringerLink

- ERC / European research summaries — “Will we run out of groundwater?” A synthesis explaining regional variability and complexity in observed trends. ERC

Final word — what we must demand now

Groundwater is slow water: it refills slowly and sustains cities, farms and ecosystems when surface water fails. Europe’s recent trends show that slow decline can go unnoticed until shortages are acute. That is why immediate, science-led action is required: measured abstraction limits, large-scale investment in water efficiency and reuse, nature-based recharge, and transparent governance that protects both communities and businesses.

For Westferry — and for every neighbourhood that depends on the wider national economy — the warning is simple: water security is now a public-policy priority. Residents should insist their councils and elected representatives treat groundwater resilience as essential infrastructure, and support measures that both conserve water and strengthen community resilience.